Dedicated soldiers helped break U.S. Army color barrier

Twice a month, U.S. Army veteran William Dyson Sr. would drive from Harlem to the Fort Hamilton Army post in Brooklyn to buy food and household supplies from stores open only to current and former military personnel. This was more than 50 years ago, but his grandson, Reggie Lewis, has vivid memories of those Saturday shopping trips — particularly their reception at the entrance to the military base.

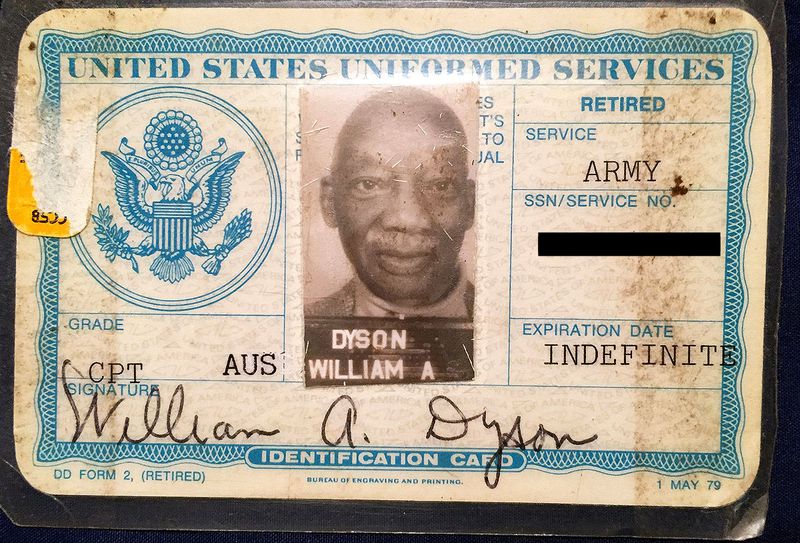

“He would present his ID and the soldier would look, and after that snap to attention with the salute,” Lewis recalled. “My grandfather would be in the car, [left] hand still on the wheel. His other hand would go up and salute the soldier.”

Lewis remembers all sorts of details about the outings, such as his grandfather’s “blue-on-blue Buick Wildcat with bucket seats and a console for the shifter.” But the salute from soldiers at the Army base’s main gate was always a high point for Lewis.

“To see this always had an impact,” he said. “It was only because of his rank — the rank of captain. It superseded anything racial. It was [showing] respect for the rank he had achieved. Whatever soldier was at the gate, that was the response he got — always.”

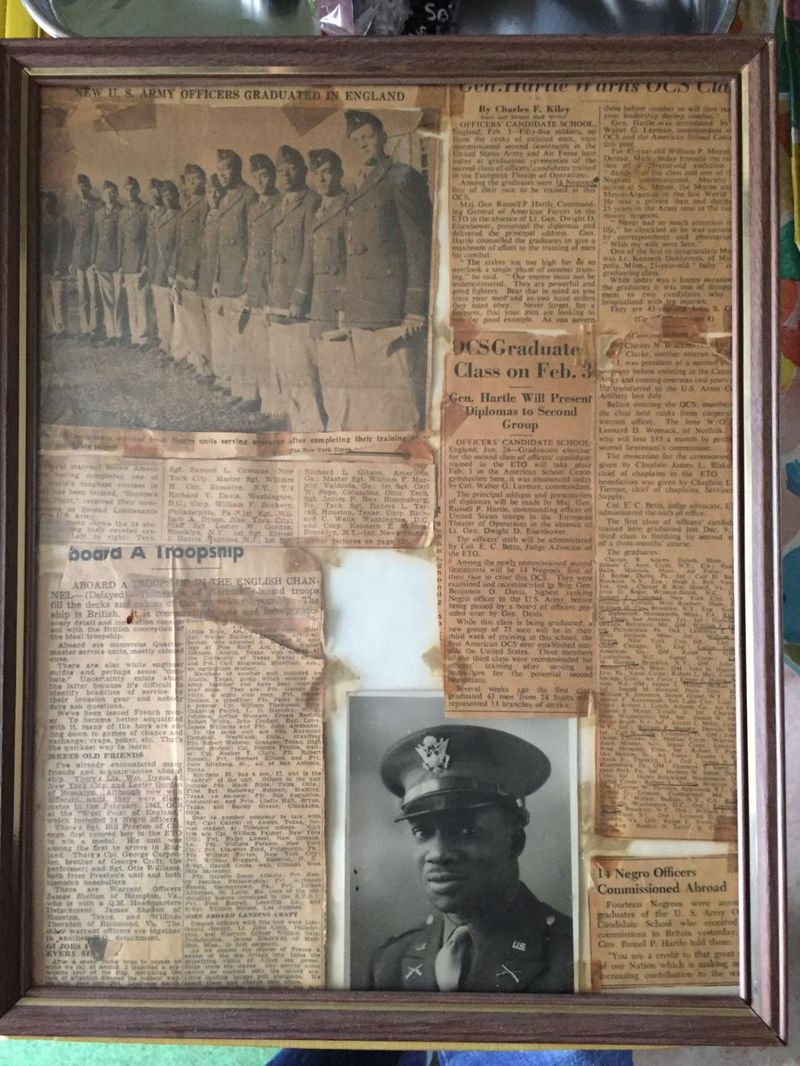

But when Dyson became an officer during WWII, it was during a time when blacks didn’t get equal treatment or equal respect.

In all of America’s wars, black soldiers’ devotion to duty and to country were strong in the U.S. military, which had long been split along racial lines with segregated white-only and black-only units. So for generations, in addition to enemy troops, black military personnel had to fight racial prejudice from some white soldiers and officers.

The book “Colin Powell: Soldier and Statesman,” by Warren Brown and Heather Lehr Wagner, notes, “Of the 370,000 blacks who served in the military during World War I, only five held officers’ commissions in the Army; none held commission in the Air Corps. It was not until 1940, when the United States was preparing to enter World War II, that a few of the barriers began to crumble.”

The crumbling started when Benjamin O. Davis Sr. was named a brigadier general in 1940, just before America entered WWII with its segregated army.

“Moreover, Benjamin O. Davis Sr. broke new ground when he was named the nation’s first black general. The army, however, refused to renounce its policy of segregation or stop relegating black recruits to service units,” the book reveals.

As he rose through the ranks from sergeant major to second lieutenant and colonel, Davis was never put in command of white soldiers. “All of his duty assignments were designed to avoid a situation in which Davis might be put in command of white troops or officers,” according to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

After his promotion to brigadier general, Davis battled the Army’s racial issues.

According to “World War in Europe: An Encyclopedia,” edited by David T. Zabecki, one of Davis’ WWII duties was to examine the “severe problems” of racial segregation in the wartime army and advise U.S. military leaders. “Davis worked to change the leadership climate within the segregated black units,” according to the book. “He conducted tours of Army posts, investigating racial incidents and defusing these problems.”

He also followed the trials and tribulations of black troops, aided in the production and promotion of “The Negro Soldier” training film, and hand-picked black candidates for one of the Army’s great experiments — an all-black officers’ training school.

After visiting the Europe during WWII at the request of commanding Army Gen. Dwight Eisenhower, Davis proposed solutions that included black American history education for all U.S. soldiers, and “increasing the number of black officers by selecting qualified individuals for Officer Candidate School.”

According to Army Center of Military History, Officer Candidate Schools were established in 1942 to address the procurement, training and retention of military personnel in the U.S. and England.

Dyson, as a member of the segregated Negro Officers Commissioned Abroad military unit, graduated from an Officer Candidate School set up in England in 1943 — the first-OCS established outside the U.S. He graduated with the rank of second lieutenant, and attained captain status by the end of his active-duty career.

“He was a by-the-books soldier. He was a kind man — always a gentleman,” Lewis said of his grandfather, who died in 1983 at 78, leaving legacy for future black military officers — and his family.

“My father instilled in me the correct way to do things, always being punctual. He was always prompt in what he did; nothing was done haphazardly,” recalled William A. Dyson 2nd, the late captain’s son. “He encouraged me and steered me into the military because it was an honorable career.” William Dyson served in Army and later became a New York City Transit police officer.

Francis Gittens-Lewis, the senior Dyson’s daughter and Reggie’s mother, agreed with her brother about how their father shaped their lives. “He was a silent giant — a beautiful person,” she said. “He and my mother had a beautiful relationship.”

His grandfather’s military experience lives on, says Reggie Lewis, who learned to be prepared and how to properly pack a truck from his granddad.

When preparing for family trips, Lewis uses using the efficient, space-saving military-roll technique.

“When we go away on trips, nobody packs the trunk but me,” he said. “I watched my grandfather do it, and I still do a military roll to this day.”

Project Details

- Category: News Clips

- Location: New York Daily News

- Date Published: FEB 09, 2017